The Two WordPress Websites and the sleazy business of Monetizing a Free Product

or, How Automattic Stole, Lied, and Cheated its Way to $ Billions

Only those unfamiliar with WordPress would not know that there are two websites claiming to be WordPress. First, there is wordpress.org, the legit home of the open-source WordPress software. And then we have wordpress.com, home to a managed web hosting service that provides a pared-down version of WordPress best thought of as WordPress Lite. WordPress.com is owned by Automattic Inc., the company founded by WordPress co-creator Matt Mullenweg.

Mullenweg created Automattic to monetize WordPress, the immensely popular content management system (CMS) he had co-created but made no money from. By all accounts, Mullenweg’s intentions for Automattic were genuine, if idealistic and a bit lofty.

Automattic’s original business model might be paraphrased “to create products and services that bolster the WordPress platform and support its user community;” namely, plugins and themes. WordPress’s plugin marketplace is extremely crowded and competitive, though, and it wasn’t long before the company had pivoted, transferring resources to its nascent managed web hosting service and blog network.

WordPress.com isn’t concerned with bolstering the WP platform or supporting the user community. In fact, the company’s actions have often appeared to oriented towards the opposite goal.

The Two-Website Problem

The Case of the WordPress Website and its Copycat Cousin isn’t a new book in the Hardy Boys series of mysteries. In truth, it is not a particularly difficult puzzle to unravel, but has been a difficult one to tell, the tale touching on many different areas of technology — search engine optimization (SEO), dot-com bias, trademark law, and the open source movement — and involving actions and behaviors the worst you can say of which is that they are deceptive, hypocritical, and self serving. One wonders whether they were inevitable given the enormity of the matter of monetizing a free product.

The simple fact at the heart of this story is that two WordPress websites, the WordPress Foundation’s wordpress.org and Automattics’s wordpress.com, operated by two legally separate and financially independent organizations, should not both exist. The products associated with each site are often characterized as two “flavors” of WordPress, complementary products in the larger WordPress ecosystem targeting different customers. This is simply inaccurate.

These are competing products, in that they are products of two separate and independent entities whose fortunes are not intertwined. Also, consumers tend to be customers of one or the other but not both. They are not part of some larger strategy for worldwide WordPress dominance. As much as Automattic’s WordPress.com service would appear to rely upon the success of open-source WordPress, they would prefer everyone believes WordPress.com is open-source WordPress. Today Automattic seems very comfortable with the idea that WordPress might die.

The plateauing of WordPress’s market share in the CMS sector over the past couple of years I think can be directly correlated with Automattic’s deceptive marketing practices, SEO irregularities, and Mullenweg’s failure as steward of WordPress in the early days of the software. All of that is discussed later in this article.

The existence of two WordPress websites, each of which earnestly wants visitors to believe is the bona fide home of WordPress causes a host of problems (to the Foundation, the WP brand, the marketplace, and new users in particular). The problems are widely dispersed. The benefits, however, enrich one company alone: Automattic.

The Failure of Trademark Laws

Trademark laws were created to redress just this type of situation, of course: that of company A working hard to establish its reputation and brand, then company B in bad faith launching a copycat website using company A’s trademark and domain name for the purpose of diverting traffic away from A’s website and creating marketplace confusion that induces visitors to buy B’s inferior and/or overpriced product, tarnishing the brand of A, diluting A’s trademark, and unduly enriching B.

Yet, in our example, we have an unusual situation in which company B owns the trademark to company A’s product. Company B does not own company A itself, or A’s product, just the trademark, but it is enough to guarantee that the remedies of trademark law are unavailable. It doesn’t hurt that company B is run by a widely beloved media darling, a “wunderkind” and “prodigy” coasting off the goodwill he banked twenty years ago when he created a beloved product.

We could characterize the two WordPress websites as just a quirk of WordPress were that word not associated with random and unforeseeable outcomes. In this instance, neither was the case. This situation was a well-planned strategy that began when Matt Mullenweg, the co-creator of open-source WordPress, registered multiple WordPress domain names for the platform in 2003, but notably failed to utilize the most valuable one — the one most users would assume was the home of WordPress, wordpress.com — to represent the software of which he was steward. Instead, he set it aside for his own future use, waiting to devise a product similar enough to WordPress that would justify its use. Again, this was well within his rights to do so, but was not an act in the best interests of WordPress or its community; it served only his own greed.

Veteran WP users have learned to put up with this foible of WordPress, even though many of them have spent countless hours (a study of the man hours that have gone into this public information campaign needs to be performed) attempting to educate newbies about the conflicting websites so people don’t wander into the wrong one by mistake. The problem is, many still do. The bigger problem is, that appears to be by design. Creation of confusion seems to be Automattic’s goal. If it isn’t, one thing is certain: the company benefits from such confusion immensely.

How Automattic Benefits from Marketplace Confusion

How exactly does Automattic benefit from confusion? Consider a visitor who isn’t sure which is the actual WordPress website. Absent no other information, they will likely assume it to be wordpress.com based on their previous experience on the web. Such is the power of Dot Com Bias.

WordPress.com, simply by existing, diverts web traffic from the actual home of WordPress to Automattic’s website. Diverted traffic translates to revenues that wouldn’t exist had the company used another domain name that more aptly described the managed web hosting service Automattic sells at WordPress.com.

SEO Irregularities

It doesn’t end there. Search engines have codified Dot Com Bias into their algorithms, such that a search in any web browser for the keyword wordpress will produce a top result of wordpress.com, the “wrong” answer to the question implied by the search (which is, What is the website of WordPress?).

This is made all the more troubling in that we know the site at wordpress.com does not go by the term WordPress sans its top-level domain of .com. That naming convention was insisted upon by the WordPress community for purposes of disambiguation, and was reluctantly adopted by Automattic. Thus, a search for keyword WordPress is far from ambiguous, and still, Google and Bing point users to Automattic’s copycat website, failing at the user intent test despite the lip service both Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp. give to user intent as the key determinant in whether a search succeeds or fails.

We are left to wonder how it can be that the above two companies, employing the best and brightest in tech, could be so utterly incompetent at a core business function. Could this fail be tied to ads purchased on their networks? Regardless, it all adds up to additional traffic diverted to the wrong website and additional revenues to Automattic.

Mullenweg hasn’t acknowledged SEO to be an issue affecting WordPress. He told WP Tavern about a similar issue in September 2023, “I don’t think the SEO concern is real… For general [WordPress] searches I’m seeing [WordPress].com five pages down.” In what alternate universe? Don’t believe me, try the WordPress search yourself. It has been confirmed in Google, Bing, Ecosia, and Duck Duck Go. Who does get it correct? ChatGPT, of course. Another nail in Google’s coffin, we can only hope.

Of course, this diverted web traffic wouldn’t necessarily translate into revenues were Automattic transparent about the relationship of WordPress.com and WordPress. But the company has a pattern of avoiding backlinks to WordPress (which suppresses WordPress’s page rank) and of implying that its website actually is the home of WordPress (keep reading, you will see). Can an entire company be entitled? Of course not, it’s the entitlement of its chief executive polluting that organization.

Lack of Transparency, Deceptive Marketing

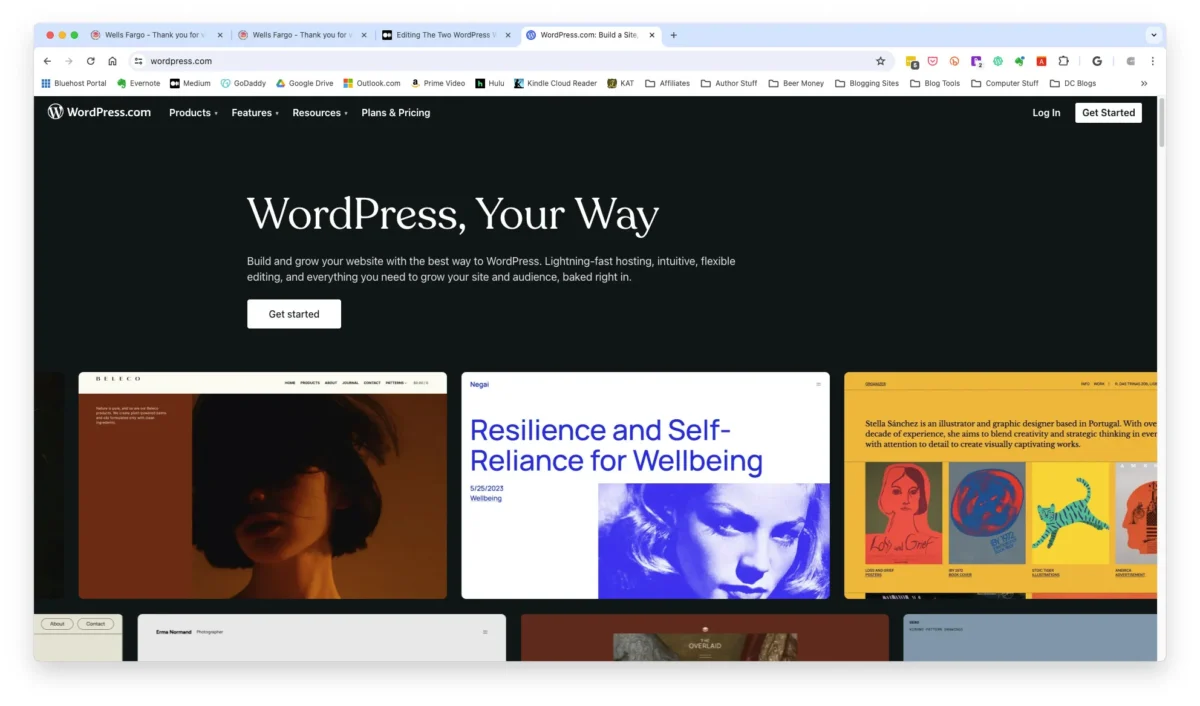

So what does this diverted web traffic encounter when they arrive at WordPress.com? If visitors remain unsure whether they have reached the “real” WordPress website when arriving at WordPress.com, the landing page won’t make it any clearer. Transparency, one of the open source principles Automattic gives lip service to, is entirely absent in the company’s flagship product.

A year ago, in 2023, Automattic’s marketing department went even further, all but claiming to visitors wandering onto their website, This is the home of WordPress. WordPress.org? Never heard of them. This was prior to scandals breaking out in the WordPress developer community, and the company has taken a step back from this openly deceptive stance.

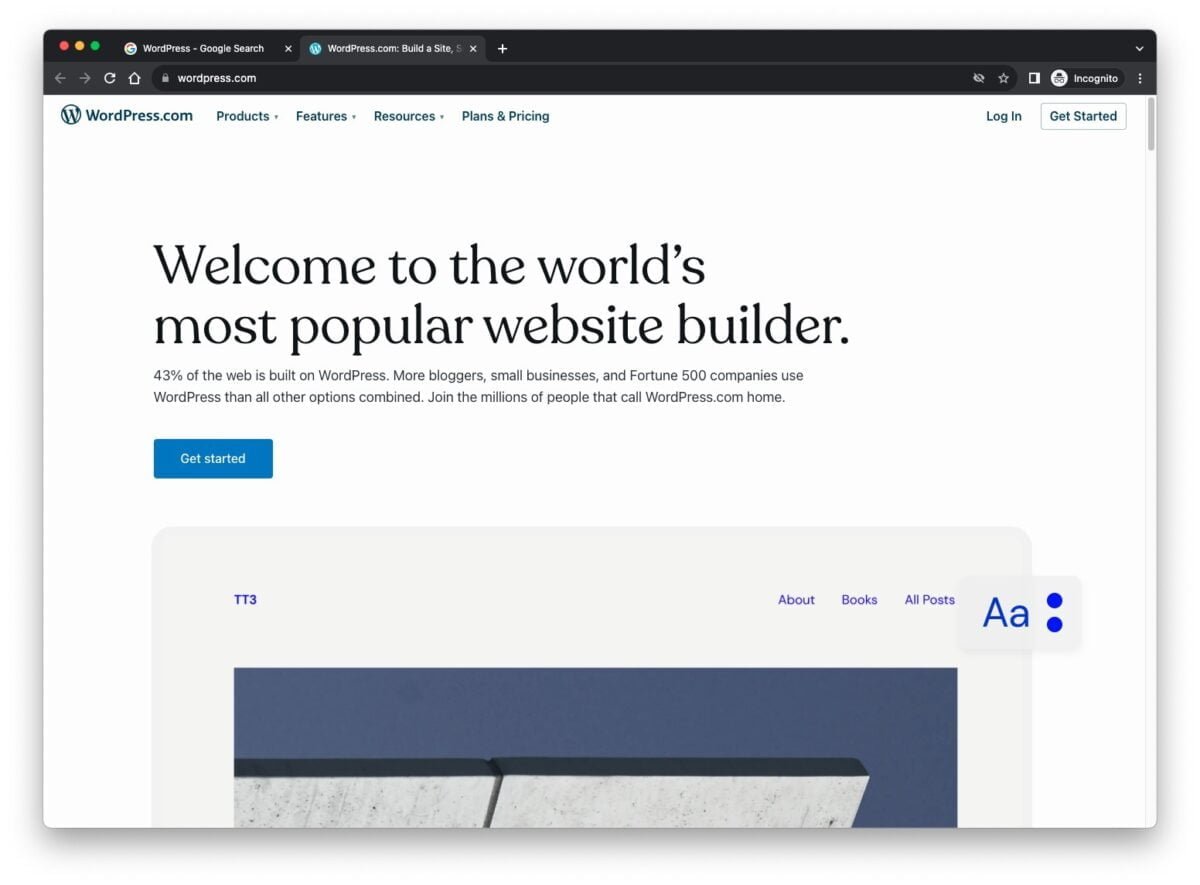

As shown below, the landing page read, “Welcome to the world’s most popular website builder,” and then included the widely quoted “43% of the web…” statistic that’s such a powerful selling point for self-hosted WordPress. Just to be clear, for that statement to accurately reflect WordPress.com, it would need to be changed to 1%, if my math is correct. Granted, that is still a large number, especially considering these are paying customers, but not very impressive next to open-source WordPress’s market share.

The interesting thing is, WordPress.com boasts some impressive stats itself, such as “one of the top 10 most visited websites in the world.” Why not post that on the WordPress.com landing page, unless the point wasn’t to sell visitors on the quality of WordPress.com, but to convince visitors that WordPress.com actually was WordPress.

Negligent Stewardship

Trademarks and .com domain names go hand in hand. One typically doesn’t own a trademark without owning the .com domain name for it. This is the domain name most often chosen to represent a company or product on the web. To possess a .com domain name and not use it for a company or product of the same name would be either stupid or negligent.

In 2003, Mullenweg chose to assign the lesser .org domain name to WordPress for reasons never specified, setting the .com domain aside. Let’s just say that no one has ever accused Mullenweg of being stupid.

Then, in 2005, Mullenweg founded Automattic — inspired, it is said, by open source ideals — as a way to finally monetize the product he had created but had been forced to give away for free. Mullenweg said his business would succeed by creating products and services for WordPress (read: themes and plugins) that strengthened the platform and supported the user community. A company with a worthy mission.

But plugin and theme creation is an intensely competitive enterprise, as Mullenweg had himself guaranteed by opening their creation to the entire WordPress user base. Today, nearly 20 years later, Automattic owns only a handful of successful plugins — Akismet, the spam filter, which it created, Jetpack, the suite of security and speed optimization plugins, which it also created, and WooCommerce, the popular e-commerce plugin, which it purchased.

That is okay, because the company’s focus has changed greatly in the intervening years. Today, by far the biggest source of Automattic’s revenues come from its managed web hosting service called WordPress.com. The company’s de facto mission is far less worthwhile than envisioned, and not beneficial to WordPress or its community of users in the slightest.

Mullenweg originally conceived of the idea during his tenure at CNET as a product manager. CNET owned a variety of domain names from acquisitions, one of which Mullenweg thought would be perfect for his business idea: online.com. CNET wasn’t convinced the idea had legs, however, and refused to green-light it.

Mullenweg left CNET to found Automattic so he could work on WordPress full time. His fledgling company’s first product was Akismet, aligned with the idea of Automattic as a company that would bolster WordPress and support the community. Its second product, however, was the same service Mullenweg had pitched to CNET, only now he was calling it WordPress and had even assigned to it the premium domain he had set aside several years prior.

Use of the WordPress trademark to represent a for-profit competing service was met with suspicion in the WordPress community. Many saw it for what it was: a way to capitalize on the WordPress name, with its extremely high brand awareness that would guarantee success for any product attached to it. Had the service been called Automattic.com, it would have had to survive on the merits of the product itself, and its reviews were less than stellar.

A Turnkey WordPress Experience?

So what is WordPress.com? As stated, technically it is a managed web hosting service that has been called a “turnkey WordPress experience.” However, the version of WordPress included in WordPress.com bares little resemblance to open-source WordPress and certainly doesn’t qualify as a content management system (CMS). At best, it is a web-based blogging tool that shares WordPress’s dashboard user interface (UI).

Over several tiers of service, for ever more costly fees, WordPress’s core functionality is returned to the tool provided in WordPress.com. It finally resembles WordPress at the tier currently called Creator, for a subscription costing $300 per year (if paid annually), more expensive than the most costly shared web hosting option for open-source WordPress. Keep in mind, WordPress.com is a piecemeal repackaging of software that is free to download and use over at WordPress’s website. This explains why WordPress.com is loathe to ever link to the real WordPress site, and why it is desperate to convince visitors that is where they have already arrived.

By offering WordPress as a web-based service, Automattic has also skirted the restrictions on derivative products in the General Public License version 2 (GPLv2), WordPress’s open source license. No distribution of software means no need to publish its source code. So Mullenweg was able to take someone else’s work product, turn it into WordPress, then sell it as a service and reap all profits from it. This may adhere to the letter of the law, but not the spirit of it.

This scam-masquerading-as-business model — as is the American way — has been extremely profitable for Automattic and Mullenweg. The company has been designated a unicorn. Like the mythical beast, a unicorn company is extremely rare. It is a privately held company worth over $1 billion (Automattic was most recently valued at $7.5 billion). Mullenweg’s net worth, meanwhile, is estimated at $400 million.

No one knows how many people have fallen for Automattic’s deceptive practices and continue to on a daily basis. A moderator of the WordPress subreddit estimated it receives ten new complaints every day from people who have signed up for service at WordPress.com believing it to be the actual home of open-source WordPress.

It’s tempting to blame the victims in this scenario: to say, if they had done a bit more research they wouldn’t have been so easily scammed. Every WordPress blog has a section or article devoted to this issue, after all. But look at the lengths Automattic has gone to to make you believe its managed web hosting service is WordPress. The company is so earnest and adamant in the assertion, it sometimes seems they believe it themselves.

I admit to some bias in this story. I was one of those ignorant newbies who fell for Automattic’s ruse. For several years I believed my WordPress.com-hosted website was WordPress. It is embarrassing to admit that now. But I witnessed first hand how Automattic’s impersonation damages the WordPress brand, because the entry-level WordPress.com service was so bad, there was no other conclusion I could come to other than WordPress was the most overhyped CMS on the planet. The raves the platform consistently received didn’t gibe with the tool I was using. Of course, that’s because I wasn’t really using WordPress. Once I learned the truth, I started to formulate this story. I could not believe no one had broken what felt like me to be an enormous scandal. The more I found out in my research, the worse it got.

Toxic Work Environment

The answer to why no one has broken this story yet may be the scariest aspect of it all. The answer is, this story has been broken. Brave WordPress volunteers have confronted Mullenweg about it, in person and over social media. His response has been a swift and brutal public excoriation of those who have done so, which has had a predictably chilling effect on anyone else speaking out against this bully and tyrant.

Mullenweg’s attitude regarding users getting confused which website is WordPress has been, Just deal with it. He stated, “ It’s much more likely like a road bump for some newbies, than an actual blocker, not unlike learning the difference between categories and tags, or how to identify a normal-looking comment that’s actually spam.” He equates trademark infringement with confusion between a category and a tag.

Mullenweg has doxxed people (published embarrassing private information about them), made degrading comments about them personally and about their careers or lack of success compared to him. An anonymous WordPress consultant told WP Tavern, “It’s a fearsome kind of punching down where the community gets stuck in the psychological position of the children of an abusive parent.”

I am a nobody in the WordPress community, I have not built a career on WordPress, I have been conned by Automattic and lost money to WordPress, but I have nothing to lose by publishing this outsider’s account of the bad behavior going on at Automattic. I am ready for petty retaliations. My interactions with Mullenweg have been friendly to date (said interactions amounting to a couple of email exchanges). I expect that cordiality will be absent in any future interactions, and that I will suffer some petty slings and arrows. So be it.

This is a fight against tyranny, obviously, but also a fight against apathy. An informal poll of WordPress users found that a majority don’t really care about this issue and haven’t been disturbed by Automattic’s actions. Hopefully when the story is clearly laid out, those sentiments will change.

Free Matt

For the record, I don’t think Mullenweg is a bad person. I actually think he seems pretty nice, and he’s cute, and he sets my gaydar off a little which doesn’t mean anything actually, straight men set it off all the time but what it does mean is that I feel a kind of kinship with him, whether real or imagined. The process of becoming a better person sometimes requires a light to be shone on some things we’d rather remain hidden. I imagine especially so for a public figure like Mullenweg. And for the inevitable movie this blog post is sure to inspire, wouldn’t a redemption story be so much sweeter than just another retread of The Social Network. Let’s prevent another Zuckerberg from happening. Free Matt t-shirts can be purchased at my website godd.in.