Are you a plotter or a pantser?

on the relative merits of a plot-oriented vs. character-focused writing style

There are two types of writers of novels: plotters and pantsers.

Plotters (sometimes called outliners) are plot focused — they outline their entire novel, often scene by scene, before beginning to write it. Their outline is a skeleton of their novel, letting them see the big picture and keeping their writing on track.

Pantsers, on the other hand, “fly by the seat of their pants” — they dream up a novel’s concept and characters, then just start writing, often with no (or little) idea of where the story is headed. This allows their story to develop organically.

There are pros and cons to both writing styles. Neither is necessarily better than the other, despite what proponents of each style claim. In fact, it is said that among published authors, there are just as many plotters as pantsers. In other words, the most important metric available — which style will get your book published — favors neither.

The question every new novelist needs to answer is simply what style is better suited to them.

Plotters

Plotters are all about planning and organizing their writing project. They are detail oriented, and like boyscouts, feel that proper planning and preparation are the keys to fending off problems down the road.

Plotters create an outline mapping out their book’s plot — the external events that happen to and around the characters — often scene by scene, from inciting incident to climax. Outlines can range from broad, one-page summaries to highly specific mind maps that present links between information and ideas, character arcs and progressions, symbolism, and more.

It is common for plotters to turn each thing that happens in their story into one simple sentence. If these sentences are written on physical notecards, they can then be moved around to tweak the plot or story flow.

The writing process for plotters is front heavy, with lots of effort at the beginning, but plotters claim the benefits make the effort worthwhile. Plotters rarely get writer’s block and tend to be more efficient than pantsers, i.e. they finish their books quicker.

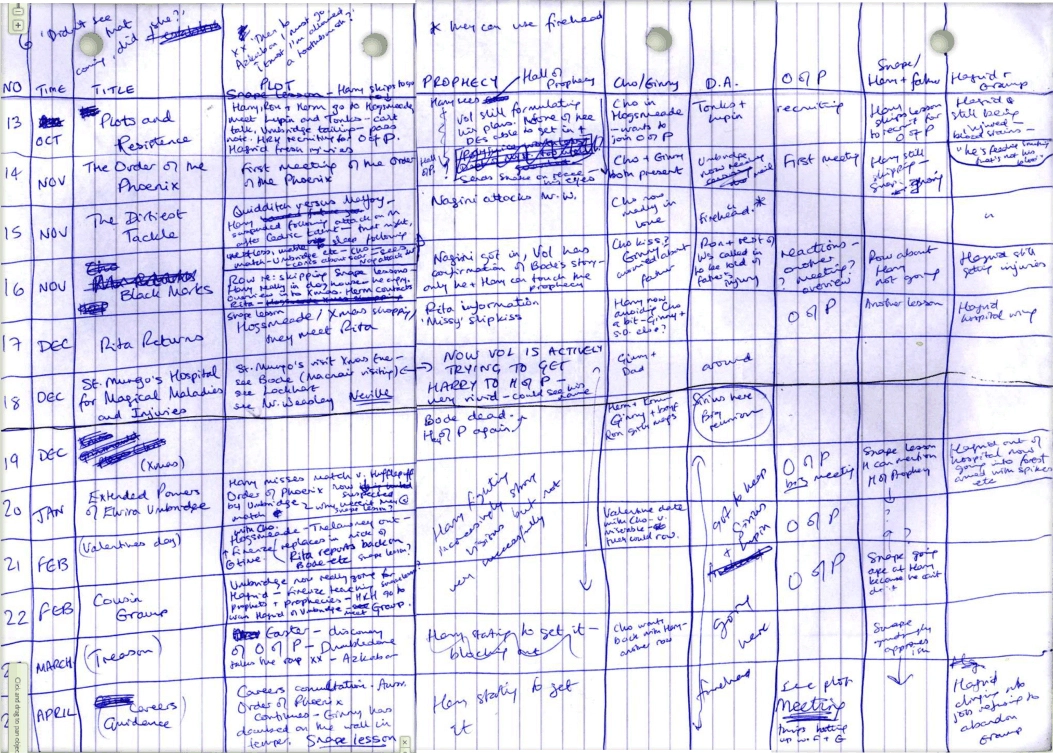

Well-known plotters include J.K. Rowling and John Grisham. An excerpt from Rowling’s outline for Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is shown below.

Pantsers

The free-spirited pantsers have a stereotypical writer’s mindset. They are creative and intuitive, and the methodical and formulaic act of plotting out a novel usually doesn’t appeal to them. They might start writing their book with nothing in mind except who the characters are and what the inciting incident is. That’s enough, because now the pantser can throw his protagonist into that situation and find out how he or she reacts. Pantsers approach the writing process as an act of discovery, almost as if they were only witnessing the narrative unfolding instead of creating it. Famous pantsters are Margaret Atwood and Stephen King.

It appears that most beginning writers are pantsers, and that many plotters start out as pantsters. Many writers have claimed to benefit from plotting their novels out even though their natural inclination was to be more laissez-faire about it. Other pantsers, such as Stephen King, claim that plotting kills their creative process, and that by focusing on plot, character is sacrificed. Both claims are probably accurate and worth heeding.

Pantsters may be better at writing characters, but their lack of a story guide makes them apt to go off on tangents that can de-rail their books. Pantsers are also prone to writer’s block, since they don’t have a guide telling them what comes next. When that happens, many pantsers simply move on to another project. In fact, it is said that one way you can tell a writer is a pantser by his collection of half-written books. When these writers do stick it out and finish these books, they probably don’t nail the landing. Stephen King’s Under the Dome feels like an example of this — a throwaway ending that’s unworthy of what came before it, intended to be audacious perhaps but just comes across like a middle finger to the reader. The point is, endings are hard, but especially so if you start writing without one in mind.

King wrote a wonderful book about his writing process, the lessons he’s learned during his career, and how writing has been an act of redemption for him, in the appropriately titled On Writing. It is a must-read for King fans and aspiring authors. For everyone else, videos on YouTube of King’s speaking engagements are pretty darn good too.

Pros/Cons

There are other pros and cons of the plotter and pantser writing styles:

PANTSERS:

| PRO | CON |

|---|---|

| They are good at creating believable, recognizable characters who respond to situations authentically and naturally. Stories are “character driven”. | They are slower writers, tend to go off on tangents since they don’t know where the story is going. Book can sometimes feel like a collection of vignettes rather than one story. |

| Complete freedom to take their story in any direction. | Easy for them to get “stuck” (i.e. writer’s block); endings are more likely to disappoint. |

PLOTTERS:

| PRO | CON |

|---|---|

| They’re able to visualize the big picture, keep story on track, and clearly present character arcs | Can lead to more telling than showing; can feel stilted or too formulaic if the outline is followed too closely. |

| Quick, efficient writers. They actually finish their novels. 😀 | Confined to their plans; if they want to change something, often the entire outline must change. |

| Don’t often get stuck, because their outline tells them what to write next. | Characters can be two-dimensional and their can seem illogical, beholden as they are to the plot. |

It is perhaps an over-generalization, but plotters and pantsers are each good in areas the other is weak. Plotters are good at writing satisfying, interesting stories that keep readers’ attention. Pantsers are good at writing characters the audience cares about.

New writers should, before committing themselves to one style or another, try out both. Writing for plot or character have different rhythms, and you may be surprised at which one suits you better. And often, trying to do things differently is how you advance to the next level.