The Fine Line between Ride-Sharing and taxicabs

This morning, Facebook, ever knowledgeable about users interests and preferences, recommended an app to me called SideCar.

Clicking the SideCar link resulted in an application page soliciting users to join its fleet of drivers with the pitch, “You drive every day. Why not get paid for it?” SideCar is a smartphone-enabled, instant-match ride-sharing service, and is one of a growing number of innovative uses of technology with the potential to eliminate additional cars from our increasingly clogged roads.

But when does a rideshare cross the line to become an unregulated taxi service, and what does this mean for consumers?

These thorny issues were addressed at the Association for Commuter Transportation (ACT) symposium, cosponsored by Mobility Lab, titled Achieving Sustainability Through Transportation Demand Management on April 18. The panel in question, presented by the Transportation Demand Management Institute (TDMI), was called “Technology-Enabled Ridematching: How it is Re-Defining Ridesharing Arrangements.” Panel members were Susan Heinrich of ICF International, Robert Werth of Diamond Transportation, Andrew Arnold of Lancer Insurance, and Paul Steinberg of Avego.

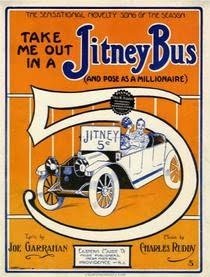

Ride-sharing, also referred to generally as carpooling and in the nation’s capital “slugging,” isn’t a new concept, having been invented in California around 1914. During this period’s U.S. recession, drivers in San Francisco with empty car seats offered rides to passengers for the same price as a streetcar fare, known as a jitney. Within less than a year, the jitney trend had spread to major cities across the United States. Streetcar operators fought the new form of competition, and local governments in many jurisdictions made the jitney illegal. Liability issues also reduced the prevalence of jitneys, and within four years of the jitney’s invention, ride-sharing had been reduced by 90 percent.

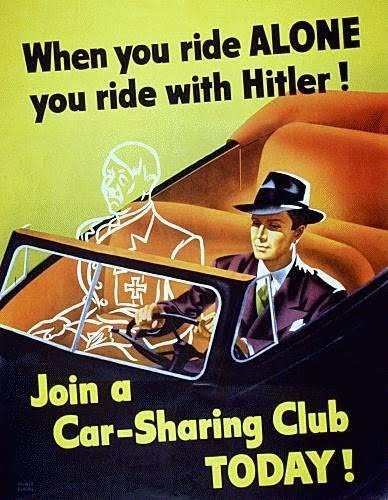

Ride-sharing made a resurgence during World War II, when resource shortages led the U.S. government (in partnership with the oil industry, ironically) to launch an ad campaign encouraging the practice. The campaign resulted in the famous “When you ride alone, you ride with Hitler” poster.

Fast forward to today, and ride-sharing amounts to about about 10 percent of all trips taken in the U.S., according to ICF’s Heinrich. It remains difficult to get people to rideshare in this country, but traffic congestion and rising oil prices have helped. Still, the vast majority of all automobile drivers travel in single-occupancy vehicles, an incredibly inefficient use of resources and a practice that is anathema to planners and environmentalists, especially since transportation constitutes roughly 30 percent of America’s energy use.

Most of the public resistance to ride-sharing seems to involve issues of flexibility. Carpooling to work results in an inability to stay late or manage a non-routine schedule. Physical carpooling billboards have been supplanted with virtual ones on the internet, enhancing efficiency in finding ride matches. And now technology has taken a big leap forward, allowing location-based technologies present in smartphones to generate an instant rideshare match, with the ability to effectively eliminate the flexibility problem.

Several apps that use this technology are SideCar, Hailo, and Lyft. Proponents of the services call them an excellent way to tap the huge “empty-seat” resource available in most automobiles. Opponents such as Diamond Transportation’s Werth, who spoke at the ACT event, refer to them as “rogue apps” that are masquerading as ride-sharing services but are actually unregulated taxi cabs. Werth cites these apps as the biggest single threat to the taxi industry in decades.

Disruptive innovations are never received by existing industries with open arms, and taxicab operators seem as vehemently opposed to ride-sharing apps as the streetcar operators were to the jitneys. Werth cited among his litany of complaints the fact that services such as SideCar use private car drivers who are unregulated, under-insured, and operating their vehicles to make a profit. Arnold of Lancer Insurance confirmed at the ACT conference that operators of paid rideshares rely on personal automobile liability insurance, and intimated that the nascent industry is one fatality away from being litigated out of existence.

Avego’s Director of American operations Paul Steinberg delineated the differences between his ride-sharing service and the ones Werth opposed. Avego, Steinberg described, is funded by the government localities in which it operates, as well as with federal DOT money. Avego charges riders $.20 per mile per seat, and pays that amount to the drivers. This is a nominal fee compared to the other services. Steinberg stated that he has no opinion on whether the ride-sharing services such as SideCar are unregulated taxi cabs, but he did state he’s quite certain they are not rideshares, because rideshares aren’t operated for a profit.

Werth, at the conclusion of the panel discussion on “Technology-Enabled Ridematching” gave Avego a passing grade. Hopefully the service will be embraced in the U.S., and that we can all expect Facebook to start cluttering our homepages with ads for this worthy service.